LAURA BEACH

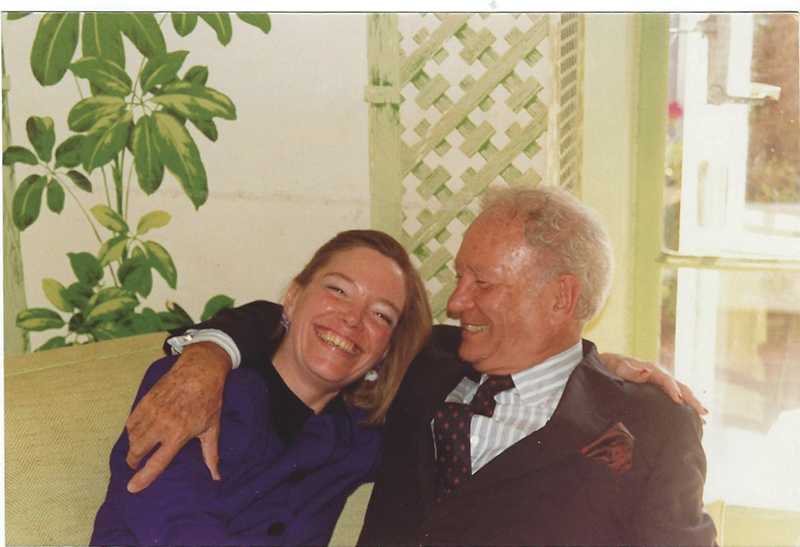

Photographer Paul Rocheleau remembers the first time he met William Nathaniel Banks Jr., the writer and collector whose thirty-seven articles were a popular feature of this publication for more than forty years. It was in Barrytown, New York, in the spring of 1982, at Edgewater, the magnificent Hudson Valley villa then owned by Richard H. Jenrette (1929–2018) and now part of the Classical American Homes Preservation Trust. Photographer and writer agreed to reconvene the following morning. “We had a beautiful day,” Rocheleau says. They clambered aboard the canoe he had brought for the occasion and paddled out into the shallows of the Hudson River, where Rocheleau shot the luminous view of Edgewater’s colonnaded facade that appears on ANTIQUES’ June 1982.

An eye for beauty, ear for language, and a commitment to capturing the nuanced historical details of his carefully selected subjects made Banks a favorite with readers and editors alike. As often as not, his stories were obliquely autobiographical. As a southerner educated in the North, he was long fascinated by the intertwined histories of the two American regions in the decades before their catastrophic rupture. Ever in search of picturesque New England villages about which to write, he was equally interested in the scattered regional expressions of an identifiably American style whose prototypes were found overseas.

Banks joined the magazine’s circle of contributors in September 1972, when his Georgia residence, known as Bankshaven— but which the magazine referred to more formally as the Gordon-Banks house—appeared on the publication’s cover. “Because physical mobility and geographical diversity have been so crucial in shaping our culture, it has seemed helpful to us from time to time to focus a cluster of related articles on a single place at one moment in history,” wrote editor Wendell Garrett (1929–2012), introducing a story by restoration architect Robert L. Raley on Bankshaven’s designer-builder, Daniel Pratt, and two companion features, one by former High Museum of Art curator Katharine Gross Farnham on the Bankshaven collection, the other by Banks himself on George Cooke (1793–1849), a Maryland-born painter patronized by Pratt. The fact that Cooke painted Edgewater’s future mistress, Susan Gaston Donaldson (1808–1866) in 1832, roughly five years after the construction of the Gordon-Banks house began, was the sort of historical connection in which Banks reveled. His second article for ANTIQUES, published in July 1974, was on the French artist Victor de Grailly (1804–1889), a painter of American views who, like Cooke, is represented at Bankshaven, the contents of which will be sold by Brunk Auctions of Asheville, North Carolina, on September 12.

“His real interest was in social history. It was the architecture first, then the people and their stories. I don’t remember anyone ever telling Bill what to write about. He chose his topics, and they were consequently connected to his heart and mind”

From its inception in 1922, ANTIQUES, under successive editors, has encouraged the writing careers of amateur scholars engaged in serious research. Garrett, who assumed the top post in 1972, helped make Houston collector Betty Ring (1923–2014) the era’s most influential scholar of American needlework. He formed a similarly productive partnership with Banks.1

“Bill was a wonderful writer and a very thorough researcher,” says Garrett’s former wife Elisabeth Garrett Widmer, herself a noted decorative arts scholar. “His real interest as it manifested itself in the many ‘History in towns’ pieces he did for the magazine was in social history. It was the architecture first, then the people and their stories. I don’t remember anyone ever telling Bill what to write about. He chose his topics, and they were consequently connected to his heart and mind.”

Born in 1924, Banks grew up in Newnan, Georgia, roughly forty miles southwest of Atlanta. His grandfather Nathaniel O. Banks started the Grantville Hosiery Mill in nearby Grantville in 1895. The company’s success assured an affluent existence for the family. Young William Jr. studied at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, his earliest recorded experience with a state that figured prominently in his writing. After serving in the military during World War II, he, by then interested in theater, completed his degree at Yale in 1948.

Banks’s affiliation with the artists’ retreat known as MacDowell (formerly the MacDowell Colony) began around 1958, when he was awarded the first of four fellowships by the organization, which had been founded in Peterborough, New Hampshire, at the turn of the twentieth century. Elected to MacDowell’s board in 1966, he served as its vice president from 1972 to 1982, and as its vice chairman from 1987 to 2018. The writers Jeffrey Eugenides and Susan Orlean are among former residents of MacDowell’s Banks Studio, so designated in 1992. Banks himself authored several plays, among them The Curate’s Play, The Glad Girls, and Season of Choice. His love of writing and writers also expressed itself in the “History in towns” features he did for ANTIQUES on Oxford, Mississippi, home to William Faulkner, and Key West, Florida, where Rocheleau and his wife, Elaine, persuaded an obviously pleased Banks to be photographed with Ernest Hemingway’s typewriter.

For his first “History in towns” in 1975, Banks chose Temple, an idyllic New Hampshire village nine miles from MacDowell, which he came to know intimately after purchasing a 1797 house there in 1961, since known as the Wheeler-Banks house. On a visit to the house, Richard Nylander, a Historic New England curator emeritus, was impressed by Banks’s extensive library and by the distinctive garden pavilion that, ever a student of eighteenth-century English landscape design, Banks had planted beyond his apple orchard in a delightfully countrified conceit. “Our youngest did a little excavation among the potted flowers, but Bill, who had encouraged us to bring our children, was very gracious about it,” says Jane Nylander, who stepped down as president of Historic New England in 2002.

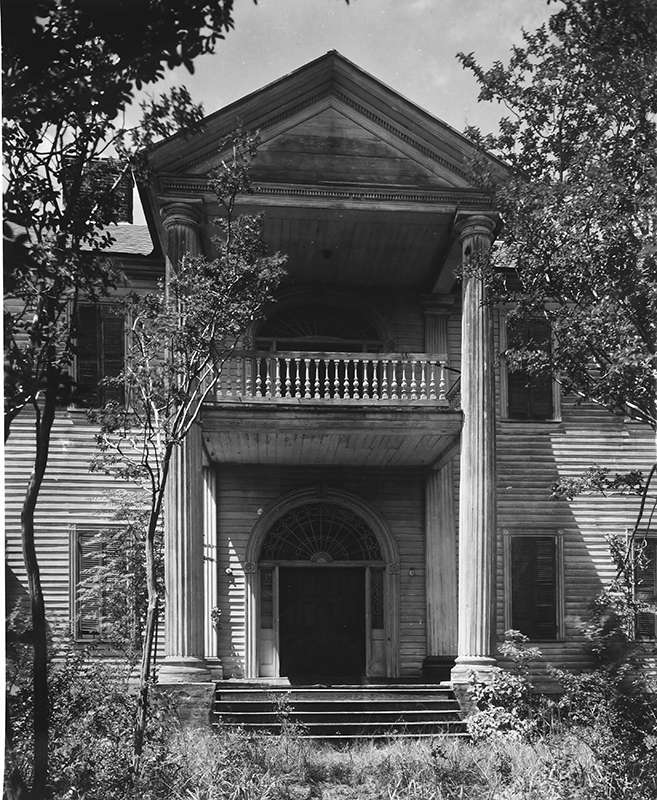

But it was the acquisition, restoration, and furnishing of Bankshaven that would become the central adventure of Banks’s life. In 1959, having seen photographs of the house taken by the Historic American Buildings Survey in the 1930s, he contacted the owner, an academic named L. C. Lindsley, who gave him a tour. As Banks writes in “A charmed life,” published in ANTIQUES in 2015, “I was awestruck by a unique house that had remained virtually unaltered for more than a century; and, I confess, I fell in love.”

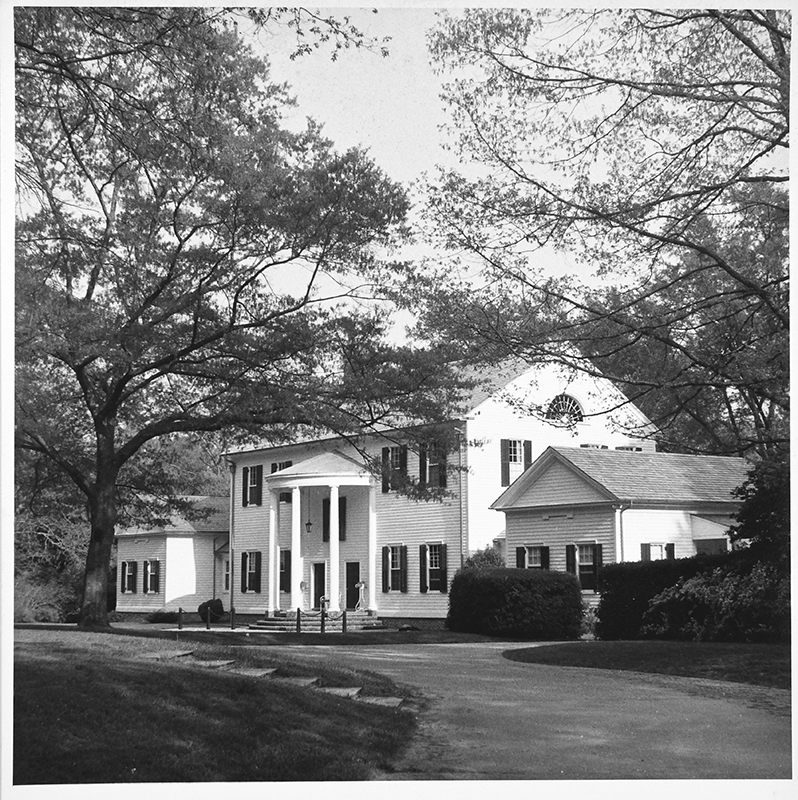

Banks’s cousin Ed Brasch witnessed the arrival of the dismantled Gordon-Banks house on flatbed trucks after the writer bought it in 1968 and moved it to Newnan, a hundred miles away (Figs. 2, 6). Enlisting the help of Raley, a 1959 graduate of the Winterthur Program in Early American Culture who consulted on both the Winterthur Museum and the restoration of the Kennedy White House,2 Banks oversaw the reconstruction of the Gordon- Banks house on his family’s property in Newnan, with its enviable views of Pearl Lake (Fig. 4).

He furnished the house, still with its original interior wood graining, marbleizing, and plasterwork, with a sympathetic assortment of American Federal and neoclassical furniture and mid-nineteenth-century American landscapes, still lifes, and genre paintings. A disciplined steward of his collections, he forswore fires in Bankshaven’s many hearths after experts warned of smoke damage to his paintings. He kept his rarely played pianoforte—a John Geib and Son of New York instrument housed in a case attributed to the workshop of Duncan Phyfe (see Fig. 8)—perfectly tuned. When Brasch asked about the logic of the latter, Banks replied, “Well, it has to be maintained.”

In late 1968 or early 1969, Banks acquired from his cousin Olive Pringle Brown a neoclassical swivel-top rosewood card table with a caryatid base, gilded and vert-antique details, and ormolu mounts (see Fig. 9). Made around 1815 to 1820 and long attributed to New York cabinetmaker Charles-Honoré Lannuier (1779–1819), the unsigned table is likely by Duncan Phyfe, experts Peter M. Kenny and Stuart P. Feld agree.

From Israel Sack, Inc., in 1971, Banks purchased a set of six lyre-back klismos chairs of about 1815 that Brunk Auctions also attributes to Phyfe (Fig. 10). “They are a classic form and very nice, though I’ve not examined them thoroughly,” says Feld, president and director of Hirschl & Adler Galleries.

While Banks mainly collected furniture from New York, he appreciated contrasting New England and Mid-Atlantic pieces. As she ascended the spiral staircase that was Bankshaven’s most arresting architectural feature, consultant Deanne Levison recalls that she caught her breath. “The second-floor landing was all done in Philadelphia classical furniture. It was a witty, erudite surprise—just so William,” says Levison, Banks’s friend and fellow Georgian.

Banks was also drawn to furniture and paintings with southern associations. One of the first important canvases he bought was Eastman Johnson’s small oil Confidence and Admiration (Fig. 14), a study for the painter’s most famous work, Negro Life at the South, which hangs in the New-York Historical Society.

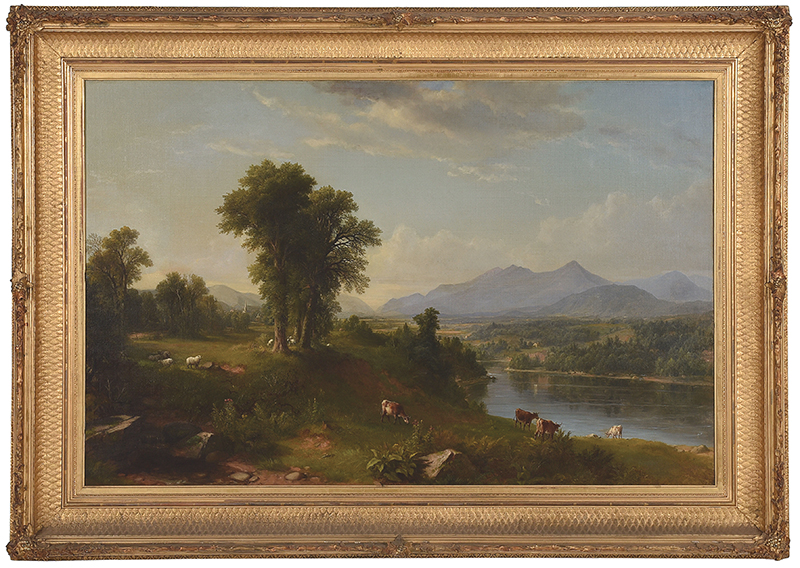

Banks’s interest in mid-nineteeth-century American life led him to the Connecticut painter George Henry Durrie and to the charming Gathering Wood for Winter, New Haven (Fig. 13), which he acquired from Coe Kerr Gallery in March 1972. He was also partial to mid-nineteenth century views of New Hampshire’s White Mountains, one notable example being Franconia Range from the South with Village of South Woodstock, New Hampshire of 1857 by Asher B. Durand that Banks purchases from Hirschl & Adler in January 1973.

For the November 1986 issue of ANTIQUES, Banks wrote about Ever Rest, the house of Jasper Francis Cropsey in Hastings-on- Hudson, New York. His enthusiasm for the second generation Hudson River school painter prompted his purchase the following month of Cropsey’s White Mountain Scenery, a glowing autumnal view of 1856, from Alexander Gallery (Fig. 12).

Skillful as a host and steeped in the rituals of gracious entertaining, Banks was a southern gentleman of the old school. “He was stylish, elegant, polite, and cultured. Being at Bank shaven and seeing how he lived transported us to another time,” says auction house president Andrew Brunk. Banks often invited friends and colleagues for lunch, thoughtfully eliminating their need to travel after dark. Described by James Landon, a longtime friend and former Banks attorney, the meal might consist of melon soup followed by sliced ham, perhaps chicken pie, asparagus, and, not to be missed, cook Amanda Dean’s superb biscuits. “A glass of cold Pouilly- Fuisse accompanied this otherwise thoroughly Southern menu, and the finale could be a berry cobbler,” Landon writes in an appreciation for Brunk Auctions.

Kenny, the recently retired co-president of Classical American Homes Preservation Trust who updated a century’s worth of scholarship on Lannuier and Phyfe with major catalogued exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1998 and 2011–2012, respectively, toured Bankshaven twice. The first time was in the mid-1990s with the Met’s William Cullen Bryant Fellows, of which Banks was a member. On Kenny’s second visit in 2012, with his friend and colleague Morrison H. Heckscher, director emeritus of the Met’s American Wing, the three men enjoyed cocktails and dinner. At the evening’s conclusion, Banks showed Kenny to a room furnished with a French wall bed that had been part of the Newark Museum’s formative 1963 exhibition Classical America, 1815–1845. Kenny recalls: “Of course, I knew this bed well from the published literature so I had a close look at it before I turned in. When I came down to breakfast the following morning, Bill was anxious to know my thoughts and asked, ‘Well, Peter, is it Phyfe or Lannuier?’ Not wanting to offend my host by telling him I thought the bed was French, I answered, ‘Beauty Rest’ and we laughed.”

As out of step with the tumultuous present as it may seem, William Nathaniel Banks Jr. believed that durable truths were embedded in the American past, truths whose lessons, learned from his own habitual peregrinations, unite us. For his last story for ANTIQUES in 2016, he revisited New Hampshire, casting an eye on Amherst, seventeen miles northeast of Temple by car. He introduced the town’s citizenry and sketched their buildings, among them the courthouse, where the young attorney Daniel Webster (1782–1852) argued, and a white-clapboard mansion on the town’s green that witnessed the 1834 marriage of future American president Franklin Pierce. In such communities, America’s promises, met and unmet, reside.

The author thanks Dana Baier, Ed Brasch, Andrew Brunk, Stuart P. Feld, Jeff Groff, Eleanor H. Gustafson, James H. Landon, Deanne Levison, Jane and Richard Nylander, Peter M. Kenny, Paul and Elaine Rocheleau, Robin Rice, Elizabeth Stillinger, Elisabeth Garrett Widmer, and Nan Zander for their assistance in preparing this article.

1Founding editor Homer Eaton Keyes (1875–1938) introduced Wallace Nutting, Esther Stevens Fraser, Rhea Mansfield Knittle, Helen A. McKearin, Ruth Webb Lee, Florence Peto, Lura Woodside Watkins, Mabel M. Swan and Nina Fletcher Little to the magazine’s pages. His successor, Alice Winchester (1907–1996), encouraged scholars Jean Lipman, who contributed more than a dozen articles between 1941 and 1987, and former ANTIQUES assistant editor Elizabeth Stillinger, whose first bylined story for the magazine appeared in 1965. 2Banks wrote about the architect and his wife in “Living with antiques: The Mary and Robert Raley Collection,” The Magazine ANTIQUES, October 2005, pp. 128–137.

Click here to see full article on The Magazine ANTIQUES